Atomic Humanism as Radical Innovation: Michael Shellenberger's Keynote to American Nuclear Society, 2017

by Michael Shellenberger

I am deeply honored by this special opportunity to address you all. I would like to dedicate my remarks to the atomic humanists around the world — from Taiwan and South Korea to Ohio and Pennsylvania to Germany and France — who are fighting to save the nukes.

1.

When Alvin Weinberg was 15, his family was destitute. The year was 1930. They had been hit hard by the Great Depression, and Weinberg’s father — a Russian-born tailor who never realized his dream of becoming an engineer — abandoned them.

Luckily, young Alvin was a math and chemistry prodigy. He entered the University of Chicago the following year, and over the next two decades worked alongside all the greats, including Enrico Fermi, Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner. By the time he was 40, Weinberg had co-invented the pressurized water reactor, the boiling water reactor, the sodium fast reactor, the homogeneous reactor, the molten salt reactor, the atomic bomb — and the American Nuclear Society.

Weinberg’s enthusiasm for nuclear’s humanitarian potential was infectious, and spread to John F. Kennedy, who visited Oak Ridge National Lab with his wife, Jackie, and Senator Al Gore Sr., just months before being elected president.

Weinberg was more than a great nuclear engineer; he was also a dedicated activist. He championed President Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace initiative with urgency in the fifties. He fought for safer nuclear in the sixties. And he warned of climate change in the seventies.

In 1979, Weinberg’s fears were realized when one of the reactors at Three Mile Island lost its coolant and partially melted. Weinberg thought there was something wrong with light water reactor designs, and his view was influential even among nuclear’s antagonists. “The Chernobyl accident was caused by design failure not operator error,” said Ralph Nader.

Nuclear never recovered from the accident. Its share of global electricity has declined seven points since its peak in 1996. French nuclear giant Areva failed in 2015 and Japanese-American nuclear giant Westinghouse, owned by Toshiba, failed earlier this year.

Weinberg’s spirit lives on in those seeking “vastly safer” nuclear designs and private entrepreneurs seeking to do for nuclear what Elon Musk did for space travel.

All of which begs the question: can radical innovation save nuclear power?

2.

Nobody doubts the policies are lacking. Last year, renewables received 114 times more in subsidies than nuclear, according to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office — a pattern that dates back 30 years. As for Elon Musk, his Space X company has won 5.5 billion in NASA contracts — and that’s on top of the $4.9 billion in subsidies he’s received for other ventures. Nuclear innovation is opposed by powerful organizations including the Sierra Club and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

Meanwhile, the crisis facing nuclear is quickening. Asia was supposed to lead the nuclear renaissance. Now, Japan isn’t restarting its nuclear, Taiwan and South Korea are following Germany, Switzerland and France are phasing out nuclear, and all while Vietnam opted for coal rather than nuclear.

There’s no secret why. Just watch the trailer for “Pandora,” the big budget disaster movie that took South Korea by storm last fall. Greenpeace — an organization with an annual budget of $350 million— coordinated protests afterwards, which helped elect a new president who is seeking to reduce nuclear’s share of electricity from 30 to 20 percent by 2030.

What does the future look like? We went through every reactor in every plant in every nation and ranked them by their likelihood of being closed found that the world could easily lose twice as much nuclear as it gains between now and 2030.

How did we get here? To answer that question, we have to go back to the 1960s, when Weinberg clashed with the Atomic Energy Commission over safety.

Upset at how he was being treated, Weinberg invited the consumer activist Ralph Nader to dinner. “I conveyed to him my sense that the AEC was not pursuing the issue of reactor safety sufficiently vigorously,” Weinberg explained.

Weinberg would almost immediately come to regret what he did. Nader crusaded across the United States training local activists on how to kill nuclear plants, or at least delay their construction. Nader was deliberately inflammatory. “A nuclear plant could wipe out Cleveland, and the survivors would envy the dead.”

Weinberg later wrote, “I am not proud of my having talked to Ralph about these matters.”

The Sierra Club joined Nader’s crusade. “Our campaign stressing the hazards of nuclear power will supply a rationale for increasing regulation... and add to the cost of the industry...” the new executive director said in a secret, internal memo.

They all advocated burning coal and fossil fuels instead. Nader said, “We do not need nuclear power...We have a far greater amount of fossil fuels in this country than we’re owning up to...the tar sands...oil out of shale...methane in coal beds...” Sierra Club consultant Amory Lovins said, “Coal can fill the real gaps in our fuel economy with only a temporary and modest (less than twofold at peak) expansion of mining.”

You might wonder: maybe people back then didn’t know coal was bad for health and the climate? In fact, it was such commonplace knowledge that the New York Times reported on its front page that coal’s death toll would rise to 56,000 if coal instead of nuclear plants were built. The Sierra Club pushed for coal anyway and even forced utilities to convert nuclear plants into coal plants in Haven, Wisconsin.

After being fired in 1972, Weinberg campaigned to save nuclear power. Along with Roger Revelle, Weinberg was one of the first American scientists to draw attention to threat posed by climate change and, also along with Revelle, urged that nuclear instead of coal plants be built. “I went from office to office in Washington, curves of the carbon dioxide buildup in hand, Weinberg wrote. I reminded them that nuclear energy was on the verge of dying. Something must be done. I almost screamed.”

3.

The people who today claim to care about climate change ignored Weinberg’s warnings. “California Governor Jerry Brown said, ‘I want the Department of Water Resources to build a coal plant.’ So we embarked on the planning of a coal plant... a dreadful prospect.”

Thanks to the efforts of Brown and the Sierra Club, California’s emissions are two and a half times higher than they would have been had he allowed the nuclear plants to go forward.

Anti-nuclear propagandists later claimed it wasn’t their doing but rather lower demand, but electricity demand rose almost as much in the 70s as it had in the 60s.

If plant cancellations were from the accidents, as is frequently claimed, then why did the backlash against nuclear not occur after the far more dangerous 1957 Windscale fire, which shot iodine-131 across the English countryside, or after the 1966 Fermi-1 sodium fast reactor fire?

The obvious difference is that by 1979 there was a well-funded, anti-nuclear movement which produced “China Syndrome,” whose release 12 days before Three Mile Island framed journalist and public perceptions of the accident as catastrophic, even though the most someone standing right at the plant gate received was one-sixth of a chest x-ray.

In the 50s and 60s, people knew nuclear power wasn’t like a bomb. It was only later that the two were deliberated mixed together such as by the organizers of the “No Nukes” concerts, putting on stage a soldier exposed to nuclear weapons testing along with a pregnant mother from near Three Mile Island. As a child this poster, which hung in my parent’s food co-op, terrified me.

Anti-nuclear leaders knew what they were doing and, toward the end of their lives, were honest. “If you’re trying to get people aroused about what is going on, you use the most emotional issue you can find,” one wrote.

And when nuclear plant construction couldn’t be stopped, it could be delayed, sending costs soaring — along with the number of federal regulations. In the end, 150 percent more nuclear plants were canceled than built.

“Unless changes are made to restore public confidence,” Weinberg warned, “the Nuclear Age will come to a halt as the present reactors run their course…”

Over time Weinberg took stock of his own role in eroding public confidence. He famously called the advanced breeder reactor a Faustian bargain requiring a “nuclear priesthood.” Weinberg later said by priesthood he simply meant highly trained professionals, like jet pilots. But Weinberg’s opponents used the statement against nuclear for decades, suggesting it is uniquely dangerous, rather than uniquely safe. “I often conceded some of their main points,” Weinberg admitted. “I was a sort of token anti-nuclear nuke…”

4.

Weinberg began to wise up in the 70s, after anti-nuclear groups killed the innovative sodium-cooled fast reactor to be built on the Clinch River at Oak Ridge ostensibly because the materials could be diverted for weapons, blow up, catch on fire and produce “hot particles.”

Their “real aim,” Weinberg wrote, “was the extirpation of nuclear energy… it was a handy and vulnerable target.”

In France, anti-nuclear activists fired five rocket-propelled grenades they had acquired from Carlos the Jackal at the Superphénix fast reactor, where they bounced harmlessly off the containment dome.

Weinberg realized that the opposition was not specific to sodium fast reactors. “Imagine the consequences from a fertilizer truck bomb detonated next to a “containment-lite” [molten-salt] reactor...truly a nuclear nightmare,” wrote David Lochbaum of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Ralph Nader admitted to PBS News that he didn’t want to solve the waste problem ”because it'll just prolong the industry, and expand the second generation of nuclear plants subsidized by the taxpayer.”

If safety and waste were the main concerns of nuclear opponents, why would they oppose reactors that address them? To answer that question, we have to go back to 1953. In his Atoms for Peace speech President Eisenhower declared the US would work with the UN to give away nuclear energy for a very specific humanistic reason: “to provide abundant electrical energy in the power-starved areas of the world.”

Over the next decade, a growing number of people began to realize that nuclear energy is limitless and humankind would thus never again be at risk of running out of energy, fertilizer, fresh water, or food. This good news came at a time of widespread fears — many of them racist, as seen here on this 1960 Time magazine cover — of overpopulation.

But something strange happened. The people who claimed to be concerned about resource scarcity from overpopulation opposed nuclear precisely because it put an end to scarcity. “If a doubling of the state’s population in the next 20 years is encouraged by providing the power resources for this growth, [California’s] scenic character will be destroyed,” warned David Brower of the Sierra Club.

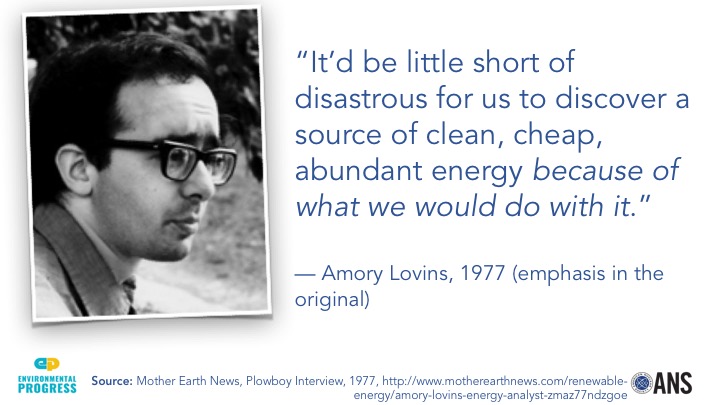

Their primary fear wasn’t accidents, waste or weapons — it was people. “In fact, giving society cheap, abundant energy at this point would be the moral equivalent of giving an idiot child a machine gun.” said Paul Ehrlich. “It’d be little short of disastrous for us to discover a source of cheap, clean and abundant energy because of what we would do with it,” said Lovins.

“I didn’t really worry about the accidents because there are too many people anyway…I think that playing dirty if you have a noble end is fine,” confessed the Sierra Club member who led the campaign to kill Diablo Canyon.

5.

In 1957, in a study for Atomic Energy Commission, researchers with Brookhaven National Labs estimated a nuclear meltdown's worse case scenario would be 3,400 immediate deaths from Acute Radiation Syndrome (ARS) and 43,000 fatal cancers over 50 years — a report that was attacked as too conservative by anti-nuclear groups.

But could there be a worse case than Chernobyl, whose reactor was unshielded, and on fire, for 14 days? According to the World Health Organization, 28 firefighters “died in 1986 due to [acute radiation syndrome] ARS. [Others] have since died but their deaths could not necessarily be attributed to radiation exposure…There may be up to 4,000 additional cancer deaths among the three highest exposed groups over their lifetime.”

What that means is that in the worst case scenario, two orders of magnitude fewer people died from ARS, and one order of magnitude fewer people will die prematurely from cancer, than predicted by Brookhaven. And of course it is six orders of magnitude fewer than the seven million people who die annually from air pollution.

Some say that what is really scary about nuclear accidents is that they can affect the public, but if that’s the case, then why then hasn’t anyone heard about the Teton dam collapse three years before Three Mile Island, which killed 11 people and caused $2 billion in damage? Or of the Banqiao dam, which killed 171 thousand people?

The data are clear. Nuclear is the safest way to make reliable electricity. The most dangerous nuclear plant is the one that doesn’t get built. When nuclear plants aren’t built, or are shut down, fossil fuels are burned, and people die.

All of which raises a problem for those promoting safer designs. The number of deaths from nuclear is so low that it would take many decades or longer to determine scientifically whether newer nuclear designs are any safer.

There’s another problem. In hyping supposed safety advantages of untested designs we unwittingly undermine confidence in, and concern for, the nuclear we have. A well-known political pundit asked me recently, “Why should I care about today’s nuclear plants closing when I keep hearing about all of these better new ones?”

It is understandable and right that we should support technological innovation for ever-safer reactors, but promoters and advocates must find ways of attracting public and private investment without reinforcing the factually incorrect, and politically devastating myths about nuclear safety. It is hard enough to save nuclear plants without having others in the nuclear community repeating misinformation suggesting they are unsafe out of the same mistaken notion that doing so will win over opponents.

6.

What about cost? Can design innovation make nuclear cheaper? Perhaps, but keep in mind that the nuclear island on nuclear plants is just 20 percent of total costs, so even if the reactor were half as expensive, little money would be saved. The historical data find that water-cooled designs, including heavy water, are the cheapest.

What is it that makes nuclear cheap or expensive? The French and US nuclear construction data offer a natural experiment. The French managed to keep the construction costs of their nuclear plants relatively steady while US costs shot upwards. Why?

According to NRC Commissioner Ivan Selin, “The French have two kinds of reactors and hundreds of kinds of cheese, whereas in the United States the figures are reversed.”

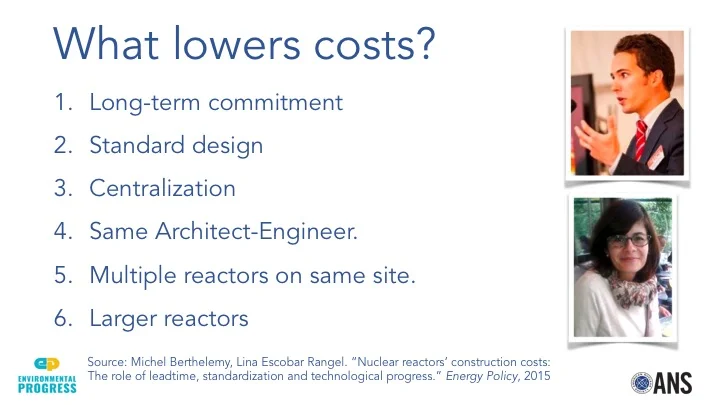

In 2015, Lina Rangel and Michel Berthélemy tapped the best and largest data set, and used sophisticated economic tools to identify six factors.

First, long-term national commitment. This is essential to creating the scale required for learning by doing. Second, standard design. Managers and workers must build the exact same design to be able to build faster next time.

Third and fourth, centralization and using the same architect-engineer. There are better results when a single entity, usually a utility, is in charge — something that was possible in France but not the US.

Fifth, build multiple units on the same site to gain learning for speed and for savings. Sixth, larger reactors take longer to build, but they produce more power without a significant increase in staff.

The data led them to a conclusion many of us might find rather harsh: “Contrary to other energy technologies, innovation leads to construction costs increases.” The constant changing of designs deprives managers and workers of the experience needed to learn and go faster next time.

When we think of radical innovation, we tend to think of changes to the design of nuclear reactors and plants. But what if changing the machines isn’t radical enough?

Debates over reactor design, size, and construction method are irrelevant so long as demand for nuclear remains low and declining. The innovation nuclear needs must be something more radical than anything that’s been proposed to day. What’s required is atomic humanism.

7.

What is atomic humanism? I would like to offer three first principles that are meant as the beginning, not the end of the discussion of what atomic humanism should be.

First, nuclear is special. Only nuclear can lift all humans out of poverty while saving the natural environment. Nothing else — not coal, not solar, not geo-engineering — can do that.

How does the special child, who is bullied for her specialness, survive? By pretending she’s ordinary. As good as — but no better than! — coal, natural gas or renewables.

Like other atomic humanists of his time, Weinberg knew nuclear was special. But he could not fully appreciate how special nuclear was given the low levels of deployment of solar and wind.

Now that these two technologies have been scaled up, we can see that nuclear’s specialness is due due an easy-to-understand physical reason: the energy density of the fuel.

Consider that the share of electricity the world gets from clean sources of energy over the last 10 years declined by the equivalent of 21 Bruce nuclear power plants, which powers Toronto, which produces about the same amount of electricity as 900 Topaz solar farms.

Bruce power sits on 9 square kilometers and Topaz sits on 25 square kilometers, so it would take 1,075 square kilometers, or twice the size of Toronto, to generate the same amount of energy with solar as with nuclear.

The environmental impacts are enormous. When they built another solar farm, Ivanpah, dozens of threatened desert tortoises, which can live to be 80 years old, were killed.

The energy density of the fuel determines its environmental impact. With higher energy densities, fewer natural resources are used, requiring less mining, materials, waste, pollution and land.

And it's increasingly obvious that only nuclear can significantly and rapidly mitigate climate change. This fact has done more to change minds on nuclear in recent years than anything else.

"If we're going to tackle global warming, nuclear is the only way you can create massive amounts of power,” said the formerly anti-nuclear Sting.

"It’s like half the people who were saying ‘No nukes!’ are now realizing nuclear is the best way to go for energy for the future. I think it’s natural to reexamine your beliefs as you age up,” said Robert Downey Jr.

Second, nuclear is human. Nuclear is people using tools to make electrons through fission. And yet the picture in our minds when we think of nuclear has no people. Where are the people? What about when we think of a nuclear plant’s control room? Now picture in your mind the cockpit of an airplane. You walk on board and you see two men. If we didn’t trust these men, we wouldn’t get on the plane. The airlines ask us to trust them, the air traffic system, and the pilots, and we do. Why then are we asking the public to trust our machines?

In the movie “Sully,” the pilot loses both his engines to bird strikes shortly after taking off. The entire drama of the film is whether Sully made the right decision. Should he have returned to La Guardia airport, or was he right to make a water landing in the Hudson? At no point did anyone suggest we should ban jet planes because they could crash. Nor did anyone demand meltdown-proof jet turbines.

I asked one of the industry’s top safety professionals, Woody Epstein, what he thought about Diablo Canyon. “It’s a great plant!” he said. “What makes you say that?” I asked. “Because the people who work there care!” At the time I thought it was the flakiest, hippy-sounding thing I had ever heard.

Then I met Heather Matteson, an environmentalist, mother and reactor operator at Diablo Canyon, and Kristin Zaitz, whom you can see here inspecting the dome, which is in pristine condition. They are like Sully and his co-pilot and crew.

Fundamentally, it’s not what makes nuclear safe, it’s who makes it safe. Every accident report says the same thing. Human factors and human-machine interaction matter most. Culture, training and discipline makes nuclear safe.

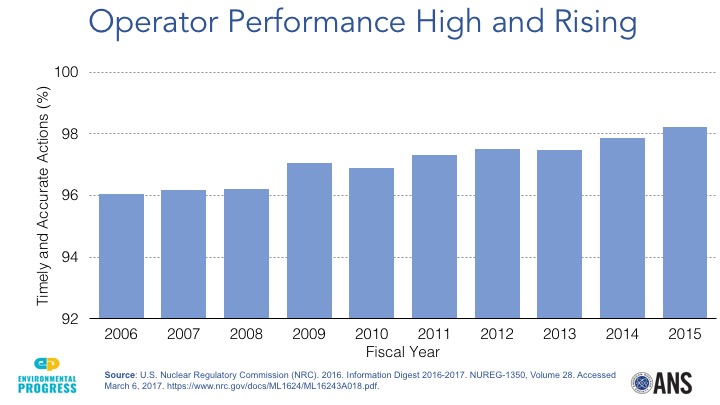

And resilience. Look at what the amazing people of nuclear did. In response to Three Mile Island, they responded resiliently and brilliantly, running the very same plants better, and raising their efficiency from 55 to over 90 percent. In what other industry is operator performance over 98 percent?

In the case of future accidents, what matters most is that operators, governments and public not panic. It is likely that, in the future, more reactors will crash and burn — just like jets. Some people may die. But because vented radiation exposes the vast majority of people to very little risk, it’s almost always going to be safer for almost everyone to stay calm and shelter on.

Third, nuclear demands action by all of us. Let’s be great professionals, but let’s also follow in the footsteps of nuclear’s founding fathers like Weinberg and be great atomic humanists, too.

Toward the end of his life, Weinberg realized that technological innovation wasn’t the only or even most important thing for the nuclear community to do. His recommendations were remarkably similar to those drawn from the study of the US and French programs. Build more reactors on the same site. Innovate — both incrementally, such as with accident-tolerant fuels, and radically, with new designs. Centralize nuclear plants under a single large firm. Professionalize and secure plants. And, most importantly, engage the public.

8.

As such, our agenda should be simple, and unifying. Defend nuclear plants. Demonstrate untested designs. And deploy standardized, tested ones.

If there’s $5 billion for Elon Musk to build a private space company, there should at least as much to demonstrate new, advanced reactor designs including the SMR and MSR, and push harder on accident tolerant fuels.

We should advocate for these things even as we acknowledge that technical fixes are unlikely to result in nuclear plants that are significantly safer, cheaper or more popular with the public.

There is no short-cut around political engagement. Nuclear energy’s opponents are well-financed and well-organized. But they have this huge achilles heel: their entire agenda rests on a rejection of simple physics and basic ethics. They are in the wrong factually and morally. As such, when they are confronted with the truth — when it is pointed out that the emperor is wearing no clothes — they lose their power.

These are the places where nuclear is under attack. Pro-nuclear forces everywhere are embattled, and need our help.

We have to get out of our comfort zones, literally and figuratively. It’s no longer safe inside the comfort zone. We’re getting killed in our comfort zone. We must travel and meet with pro-nuclear resistance fighters wherever they are. We must lend them material, psychological and spiritual aid.

It’s time for action. We have to move. We must confront the truth, and confront the threat. By standing up to Sierra Club, NRDC and other anti-nuclear greenwashers, we saved nuclear plants in Illinois and New York. We must stand up, and we must sit down. For many of you, blocking the entrance to the headquarters of NRDC might be too radical an innovation. Happily, not for these atomic humanists, nor their UC Berkeley nuclear engineering professors, who applauded Chris and Joey’s action.

As a pro-nuclear environmentalist, ANS member, and atomic humanist, I’m excited to work with all of you to realize our shared vision, which is to “be the recognized, credible advocates for advancing and promoting nuclear science and technology." This is going to be a grand adventure.

Thank you very much.